My Life in Amsterdam: Part II

I have now been living in Amsterdam for almost six months, long enough to get a feel for Dutch culture and experience many aspects of it firsthand. Though I’m still shaky on a bike and my Dutch is laughable, I’ve tried my best to settle into the lifestyle. Yet, confusing things still jump out at me every so often and I don’t think I’ll every truly understand what makes many of these customs and traditions tick.

* * *

I’ve never been on a battlefield, but I’d imagine it’s a lot like Amsterdam on New Year’s Eve. Explosions in every direction — relentless flashes in the sky, tremendous earsplitting bangs, sudden crackles of light, shouting, laughter, and smoke. Every year, fireworks go on sale just before New Year’s. But these are just the rinky-dink firecrackers that can barely keep a child entertained; the real fireworks connoisseurs get their wares in Belgium, where you’re free to buy the stuff that’ll take your fingers off. On New Year’s Eve, despite the cold and drizzle, the pyromaniacs ran free, with no oversight or regulation. Fireworks shot into the air, barely clearing the gables of apartment buildings packed with spectators. Sensory chaos prevailed. It reminded me of 4th of July…except that it was snowing and the fireworks displays were put in the jittery hands of a drunken public. It was a grass roots approach ensured that no nook in the city went untouched by stray sparks or gunpowdery haze.

Against the roar of fireworks, Amsterdam’s problem with homelessness is a quiet one. I rarely see homeless people or panhandlers while walking around the city, though I’ve heard that many sleep under bridges and sneak onto boats moored in the canals. Many organizations, mostly religious ones, have safe homes and work programs in place. Drug addiction, specifically heroin, is still a major problem in this community, though less so than in the wild 1970’s. I was surprised to hear about some of the peculiar strategies the government has enacted while dealing with homeless addicts. They used to dole out limitless methadone on the streets, and now they distribute pure heroin to many addicts, effectively keeping them subdued throughout the day.

I believe The Netherlands’ unusual position on drugs is largely shaped by a recurring theme in Dutch history: if something is illegal, the authorities will look the other way as long as it’s harmless, lucrative, and productive. It’s a constant struggle between what is moral and what is practical. The best example of this mindset is marijuana: though technically illegal in The Netherlands, the Dutch government realized that actually enforcing the ban would devastate Amsterdam’s tourism industry and lead to violent, drug-related crimes.

Centuries ago, the look-away policy sheltered pious Catholics from strict Protestants. Anne Frank was not the only resident of Amsterdam forced to hide in the attic as a result of religious persecution. Protestantism and its austere values had Catholics practicing in secret for hundreds of years. The Ons Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic) is an impressive Catholic church, built across the connected attics of three canal houses. Most people knew that covert Catholics congregated there every Sunday, but despite occasional complaints from nosy neighbors, the city government never cracked down (after all, it wasn’t hurting anybody, and Catholics were productive members of Dutch society).

What struck me about this church was the view. I could track Amsterdam’s religious history through the windows of this attic. Through one window, the Oude Kerk — Amsterdam’s oldest church. This was the place fifteenth-century sailors would go to save their souls after a sin-filled night in the Red Light district. But during the Reformation, the Oude Kerk (and many other churches in The Netherlands) was converted to Protestantism, stripped of all its ornate, Catholic-ness. Catholics began to practice in clandestine churches, like the place I was standing. Through a different window, I could see St. Nicholas — currently Amsterdam’s primary Catholic church, built in the late nineteenth after Amsterdam returned to a policy of religious tolerance.

Speaking of Christianity: Sinterklaas. Rather than using Christmas to celebrate Santa Claus (the American way), the Dutch set aside December 5th just for Saint Nicholas (who the Dutch call Sinterklaas). I barely understand Christmas, so it’s no surprise that Sinterklaas is the most confusing piece of Dutch culture I’ve encountered in my time here.

From what I’ve gathered, Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of children and of Amsterdam. He comes from Spain, brings sweets and presents to children, and has an assistant named Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). Piet travels down chimneys to distribute small cookies (pepernoten) to good children and to stuff bad children into sacks that he smuggles back to Spain. It seems to me that Zwarte Piet is the real star of the show; he is beloved in The Netherlands — even more so than Sinterklaas. At the Sinterklaas parade, I saw an army of hundreds of Zwarte Piets dance merrily down the streets, throwing cookies to grinning children, making music in giant marching bands, and rappelling off buildings (though I don’t know where that last tradition came from). He even has his own Gangnam Style spinoff, Zwarte Pieten Stijl.

Zwarte Piet dresses in eccentric medieval clothing and blackface. I’ve heard different sides to the story of his black skin: many people suggest it comes from the ashes and soot of the chimneys, while others point out that Piet is a Moor. Incidentally, among some groups, Piet has become the source of intense controversy. While I personally don’t consider Zwarte Piet a maliciously racist symbol, he does kind of give me the creeps.

Enough about religion, let’s talk about interior design. No matter where you go here, the furniture is so…Euro. I don’t know what I was expecting; this is Europe after all. But still, I’d always thought the pod chairs and colorful pipes were only seen in design magazines and in The Jetsons. Everything either looks like it comes from 500 years in the past or 50 years in the future. While the Dutch celebrate the rich, long history of their churches and canal houses, it seems like every government and institutional building in the Netherlands — the immigration office, the library, the bank — tries instead to resemble an IKEA display or a Mondrian painting. I’m not complaining; back home, government buildings and banks generally embody pure gloom. The stark contrast is refreshing, and it’s always nice to see bright orange couches, lime green walls, and oddly shaped counters.

There is a lot of Dutch food that I love. As a man who enjoys a full belly, I appreciate that Dutch cuisine is centered around heavy things like meat and potatoes. The cheese and beer are excellent, and I can frequently order them together at bars, along with bitterballen (which I can only describe as balls of deep-fried meat gravy). When my sweet tooth acts up, I go straight for the poffertjes, which are like little pancake puffs, covered in butter (and they’re even better than they sound). There are french fries everywhere, smothered creamy, unhealthy sauces. And I’ve become obsessed with vla (a thin pudding), it can’t be beat–especially after throwing in some chocolate sprinkles (hagelslag) which the Dutch seem to put on everything.

But there is another side of Dutch food — a side that confounds and slightly disgusts me. Salted licorice literally tastes like boogers. I could do without the herring, which is too fishy even for me. The sandwiches are a constant source of disappointment: many times it’s just two giant pieces of bread with a tiny slice of cheese or a cookie (yes, a cookie) in the middle. Occasionally, the croquettes have horse meat inside. And for some reason, people here drink buttermilk (karne melk) straight. I like butter and I like milk, but buttermilk tastes rancid. Throughout The Netherlands, it’s not uncommon to see adults publicly drinking buttermilk from a carton.

While I like Dutch food overall, I chronically suffer from a lack of good Mexican food. Döner Kebab makes for a decent substitute, but I still miss dirt cheap gigantic burritos. I also miss greasy, American-Chinese food. Chinese food here is excellent, but too authentic; sometimes you just want some Orange Beef.

* * *

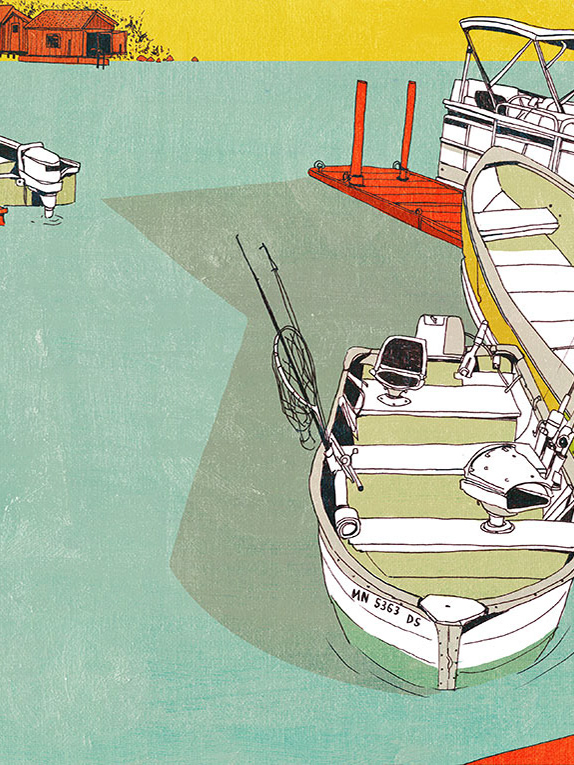

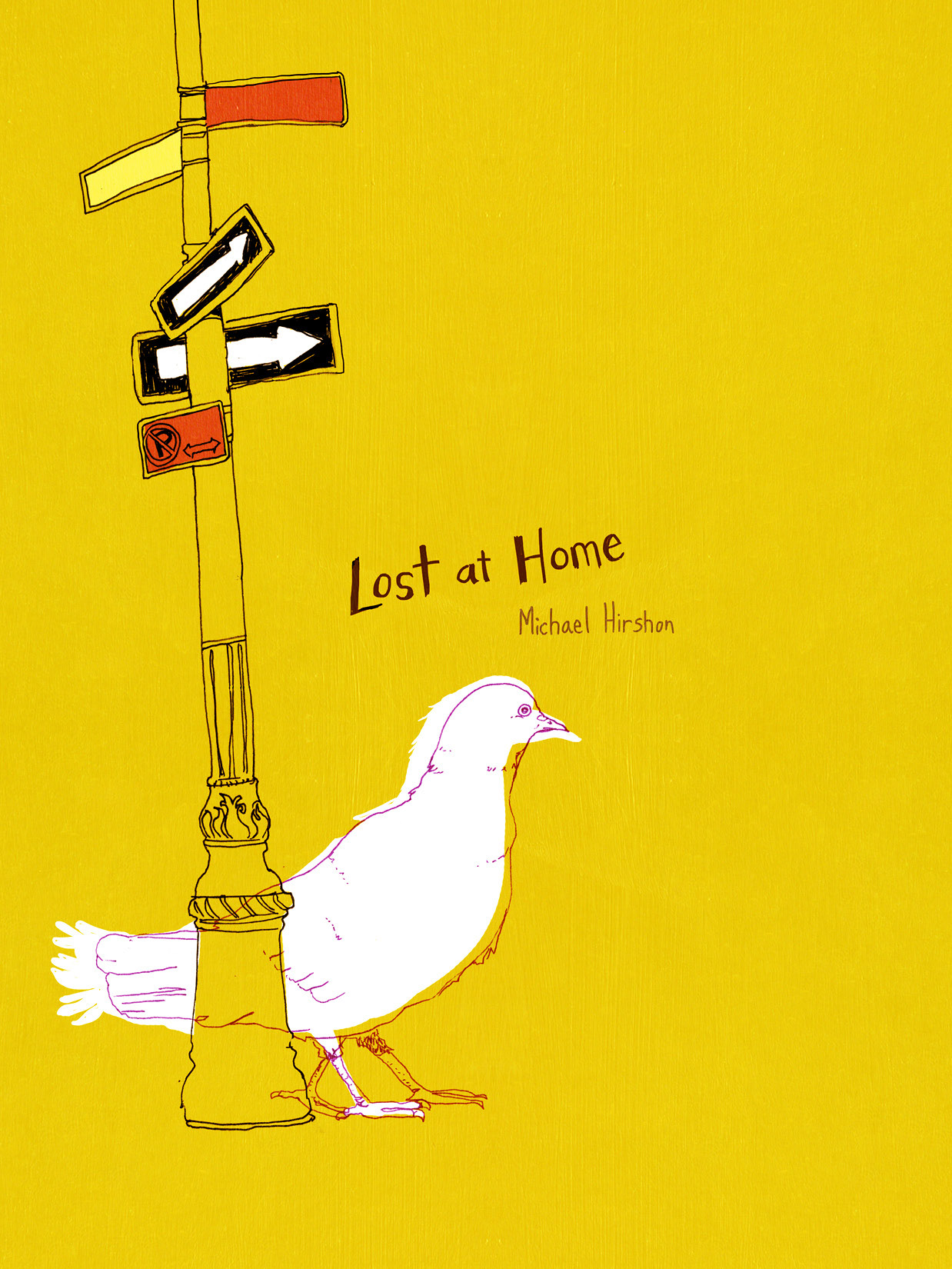

I spend quite a bit of time racking my brain, trying to figure out what exactly is going on here. What was that bang? (it was a kid setting off a firework 2 weeks after New Year’s) Why does the ketchup taste like curry? (probably due to a history of Dutch colonization in the West Indies) Why is a full orchestra floating by our apartment on a boat? (still don’t know) Even though I’m frequently perplexed, it’s been truly helpful to slow down and process my Dutch life through a sketchbook.